The cost-effectiveness of a conveyor belt depends entirely on the length of its working life along with a minimal need for stoppages to carry out running repairs. Thanks almost entirely to one or two leading European and North American manufacturers, conveyor belt construction and rubber technology has advanced enormously in recent years with today’s leading brands providing a working lifetime up to five times longer than their competitors. Unfortunately, the majority of operators continue to replace belts far more frequently than should be necessary because the belts they are buying become worn out before their time.

Belt longevity – the rubber quality is the key

The biggest influence on the performance and longevity of a conveyor belt is the quality and resilience of its rubber covers. The key rubber properties are usually resistance to abrasive wear, cutting, gouging and ripping & tearing. The wear properties of ALL abrasion resistant conveyor belts should be at least DIN Y standard (ISO 4649/ DIN 53516 test maximum 150 mm3 loss) to achieve reasonable economic longevity (lowest lifetime cost). If sharp, abrasive materials are being conveyed then higher-grade DIN X covers (maximum rubber loss under testing of 120 mm³] may be more suitable due to a higher resistance to cutting and gouging.

Faced with continual surface wear and damage problems, increasing the cover specification may seem logical but not necessarily the best solution. One manufacturer’s DIN Y (ISO 14890 L) can often be far more durable and wear resistant than another manufacturer’s DIN X (ISO 14890 H) or even DIN W (ISO 14890 D), which are usually reserved for extreme duty applications. Laboratory testing regularly exposes instances of belts at the lower end of the price/quality spectrum claimed to be DIN X or DIN W, but which fail to achieve the DIN Y standard.

A highly experienced application engineer friend of mine recently confirmed the truth of this when he was inspecting a belt supplied by Fenner Dunlop in The Netherlands that was running on a particularly aggressive application in Finland. “I measured the top cover thickness using an ultrasonic thickness gauge and I was amazed to find that only 7%, about 0.5mm, of the cover had worn away after more than 2 years service”.

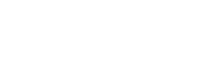

Wear testing

The test method for abrasion (ISO 4649 / DIN 53516) is actually quite simple. Abrasion resistance is measured by moving a test piece of rubber across the surface of an abrasive sheet mounted on a revolving drum and is expressed as volume loss in cubic millimeters. The most important thing to remember when comparing abrasion test results (or promises!) is that higher figures represent a greater loss of surface rubber, which means that there is a lower resistance to abrasion. Conversely, the lower the figure the better the wear resistance. For abrasion resistant belts, the absolute maximum volume loss should not be more than 150 mm³.

Comparing an offer from one manufacturer to another is made difficult because the technical datasheets provided by manufacturers and traders deliberately only show the minimum demanded by a particular test method or quality standard rather than an indication of the expected performance of the belt they are offering. The only exception to this is Netherlands-based Fenner Dunlop who show the average results achieved during the strict quality testing they carry out on every batch of rubber they produce.

Thicker is not normally the answer.

Although thickness can be an important consideration, the actual wear resistant properties of the rubber are far more important. If it is felt necessary to increase the cover thickness to compensate for premature wear, then that is a sure sign that the level of abrasion resistance is inadequate. As well as good abrasion resistance, good quality rubber will also have superior tear strength (measured as either N/mm2 or MPa) so that it can better resist rip and tear propagation.

Crucially, wear and tear caused by abrasive action, cutting and gouging, is significantly accelerated due to degradation caused by the unavoidable exposure to ground level ozone and ultraviolet light.

Accelerating the wear process

The serious short and long term damage caused by ozone (O3) and ultraviolet light (UV) is not limited to high altitudes or sunny climates. Ground level, “harmful” ozone, is created by the photolysis of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) from automobile exhaust and industrial discharges. The reaction is known as ozonolysis.

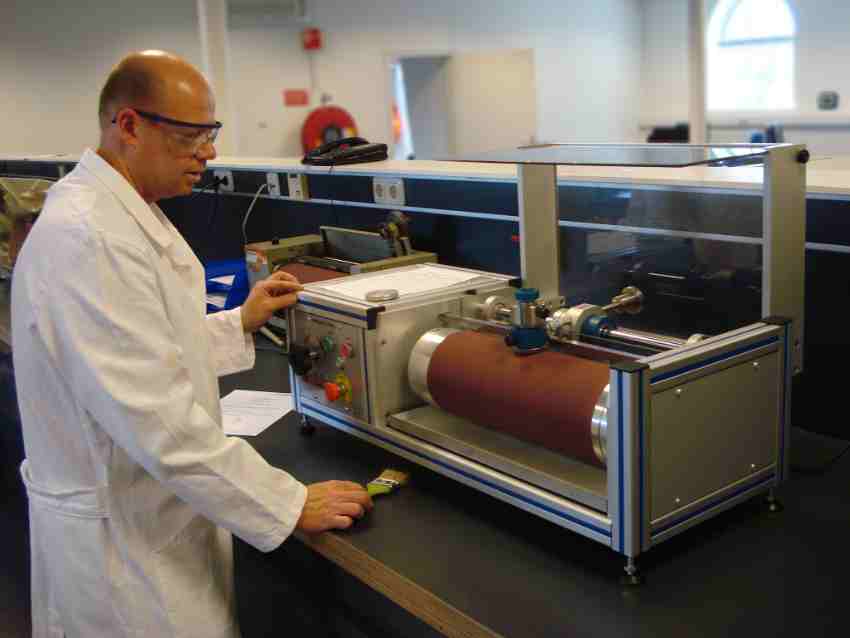

Tiny traces of ozone in the air attack the molecular structure of rubber. It increases the acidity of carbon black surfaces with polybutadiene, styrene-butadiene, nitrile and natural rubber the most sensitive to degradation. The first signs are cracks that appear on the surface of the rubber. Further attacks occur inside the freshly exposed cracks, which continue to steadily grow until they complete a ‘circuit’ and the product separates or fails.

Ultraviolet light from daylight and fluorescent lighting also has a seriously detrimental effect because it accelerates rubber deterioration by producing photochemical reactions that promote the oxidation of the rubber surface resulting in a loss in mechanical strength. This is known as ‘UV degradation’. Rubber belts that are not fully protected against ozone and UV can start to degrade as soon as they leave the production line. Despite its crucial importance, ozone and UV resistance is very rarely, if ever, mentioned by traders or manufacturers.

Ozone and ultraviolet damage is entirely preventable simply by the addition of antioxidants to the rubber compound mix. Despite this, tests show that more than 80% of belts sold in Europe fail within only 6 to 8 hours of the 96-hour EN ISO 1431 test. This is because most manufacturers see antioxidants not only as an avoidable cost but also something that significantly impacts the sale of replacement belts. My advice is not only to make ozone & UV resistance according to EN ISO 1431 a required part of the belt specification but also to closely examine the belt for signs of surface cracking as soon as it arrives on site.

The primary target for cost-cutting.

The rubber is always the primary target for manufacturers to cut costs and improve their price competitiveness because it represents some 70% of the mass and 50% of the raw material cost of a conveyor belt.

Apart from the total omission of key ingredients such as the antioxidants needed to protect against ozone and UV, other methods include using large proportions of recycled scrap rubber of highly questionable origin, unregulated, low-grade raw materials, and the substitution of essential polymers such as carbon black with much lower grade versions. Such practices allow unscrupulous manufacturers to massively undercut the prices of the few remaining manufacturers at the quality end of the market.

Not cheap at half the price.

Fitting and replacing two or three ‘economically priced’ belts rather than fitting a good quality, much longer lasting belt is invariably a false economy. Fortunately, one of the best indicators of the quality is the price, so it is always worth being suspicious and checking and comparing the original manufacturer’s specifications very carefully as well as asking for documented evidence of origin, EU regulatory compliance and anticipated performance data.

Author: Bob Nelson